By Magdalene Klassen

Digital technologies have reshaped access to historical sources and methods of sharing our research. Though computer directories maintain the vocabulary of an earlier classifying structure in the form of files and folders, historical research has been reorganized by the scale of data possible, text-searchability, and sharing across geographic limitations. In our department, some professors are also drawing on new methods and technologies to reshape the organization of historical research and teaching. “History Lab” courses offer students the chance to conduct their own research as a part of a larger project chosen by the professor. Collaborative, experimental, and often digital, History Labs introduce students to new methodologies while giving them a chance to work with primary sources up-close.

Lab: Making Maps of Mexico Lab

In her first “Making Maps of Mexico” lab, Professor Casey Lurtz asked students to help her convert huge swaths of data about late-19th century Mexican agriculture into “StoryMaps.” Using these interactive digital maps, students learned how historical narratives emerge from archival data. Each student had their own focus—railroads, indigenous map-making, climate change—but together, their work offered a richer understanding of turn-of-the-century life in Mexico.

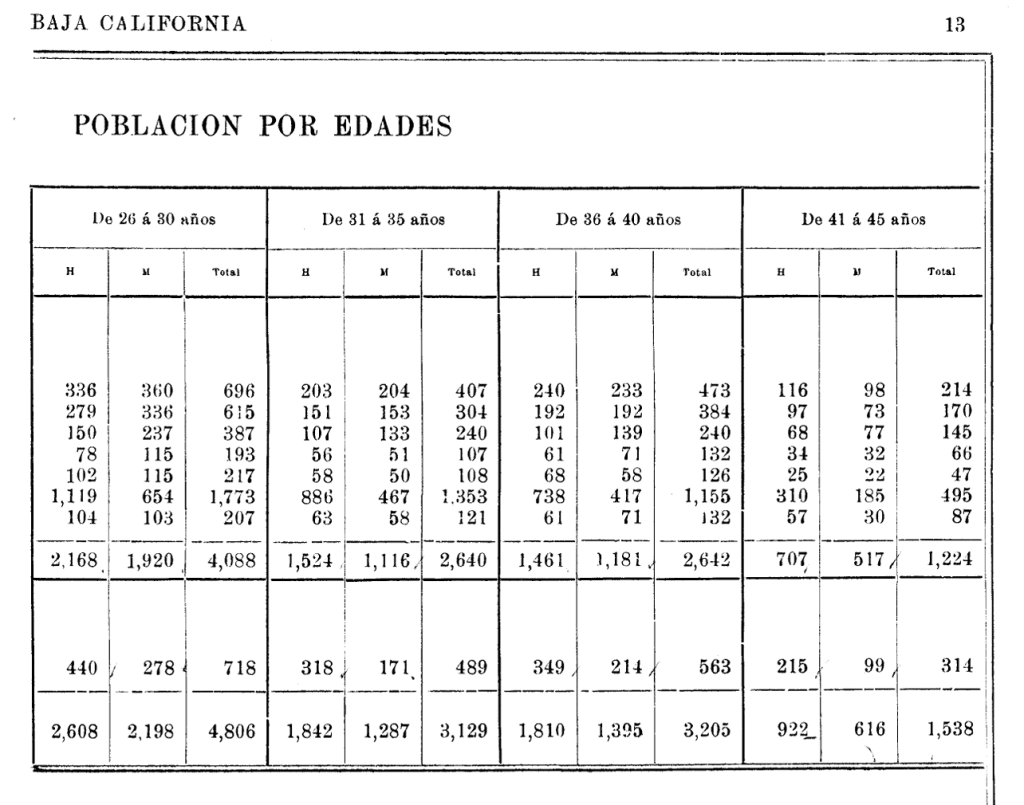

This year, students are working to analyse the 1895 and 1900 Mexican censuses. In the process, they learn to think critically about data: from the historical and always contextual production of statistics to the gaps and elisions of digitization and searchability.

Lab: Hard Histories at Hopkins

Through the Hard Histories at Hopkins project, a collaboration with the SNF Agora Institute, Professor Martha Jones is leading a similar effort. The Hard Histories lab is a collaboration among faculty, graduate students, and undergraduates, working together to interrogate the inherited understanding of the university’s past. “Blending research, teaching, public engagement, and the creative arts, Hard Histories aims to engage our broadest communities—at Johns Hopkins and in Baltimore—in a frank and informed exploration of how racism has been produced and permitted to persist as part of our structure and our practice,” their website explains.

For undergraduates in the lab, participating in Hard Histories offers a chance to link their own archival research to broader discussions about racism, inequality, and power in the US and in universities in particular. At a time when the humanities have too often had to defend their value, the Hard History lab offers undergraduates an up-close understanding of the importance of historical study.

Lab: Asian Diaspora of Baltimore

Professor Yumi Kim’s lab on the Asian diaspora of Baltimore is a similarly place-based project, exploring a history that is little known even among Asian-descended communities in the area. The course will ask “how and why local histories of Asian American and diasporic peoples have been suppressed, as well as to engage in collaborative and reparative work in response to such suppression.” Students will pursue original research in connection with local archives and organizations and through workshops with community collaborators and guest speakers. In addition to training students in how to do historical research, participants will learn to think critically about how to organize and share their research with the public.

Together, they will design and create a method of making their findings publicly available online to “help generate future local histories of Asian American and diasporic people in Baltimore. Crucially, enrolling in the course will not be the only way of engaging in this effort: through the CRAAV Research Collective, undergraduates who are interested will be able to assist in the project. History labs are an excellent way to bring many people’s focus and skills to an understudied area and develop a very strong base of historical knowledge.

Labs focusing on Black and diaspora research

Dr. Jessica Marie Johnson’s ecosystem of labs includes Black Beyond Data, LifexCode, DH against Enclosure, Diaspora Solidarities Lab, and within that at JHU the Community Knowledge Lab. Making use of academic digital capacities is a project that uses technology against “sociological boundaries” of historic statistical and data analysis. These projects ask how “how Black and Indigenous knowledge can be part of and inform the historical research work that we do.”

In turn, the labs respond by prioritizing work that is useful to the public historians and community members who help to create it. This summer, Dr. Johnson took a team to New Orleans to consult with local historians and share the digitizing work she is doing with French and Spanish documents relating to slavery in the region in the eighteenth-century. As she explains, “if we flip and have the authority going in the other direction, thinking about what communities might need, we learn differently. Things we need to learn in the first place, but we actually learn something that has a structural impact.” The lab system allows members to pursue a multitude of projects at once asking different questions related to shared commitments.

As Dr. Johnson suggests, the work of digital humanities “is essentially community.” Collaboration is what makes Dr. Lurtz’s census analysis possible. Synchronously studying Hopkins’ Baltimore history at different time periods underpins Dr. Jones’ Hard Histories project. Dialogue across community, archive, activism, and classroom is the foundation of Dr. Kim’s research collective. Dr. Johnson’s many projects resisting enclosure create a vital framework for inference and conversation. In the laboratory, communities share the work of telling history.